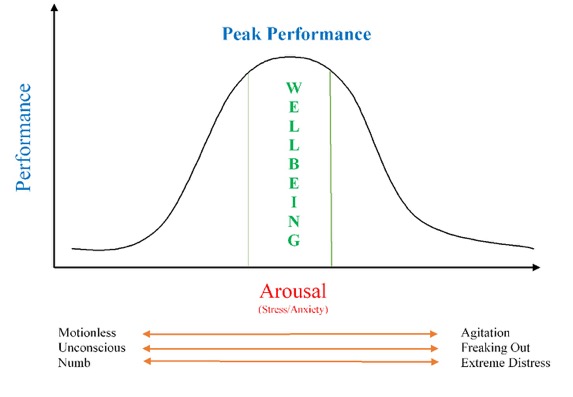

The answer is they lack well-modulated arousal in an optimal range where they think at their best, feel at their best, and perform at their best.

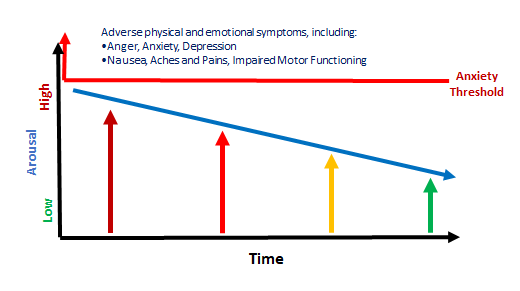

According to the theory of homeostasis the brain adapts the internal state of the child to the external world. You might be forgiven, then, for thinking that once you take them out of the inadequate care environment and place them in a safe and nurturing one their motor should slow down. Sometimes it does, and the child is settles and thrives. Much of the time, however, this state of high arousal is maintained by several factors, both internal and external. External factors include:

- Contact with birth parents, especially where that contact occurs in settings and in situations where they have the same or similar experience of their birth parents;

- School (or kindy or childcare), where there are competitors for adult attention and responsiveness, or when there the child’s heightened emotions and behaviours are not well-understood and responded to therapeutically; and,

- Our own feelings in response to the child’s heightened arousal and associated emotions and behaviours.

Internal factors include:

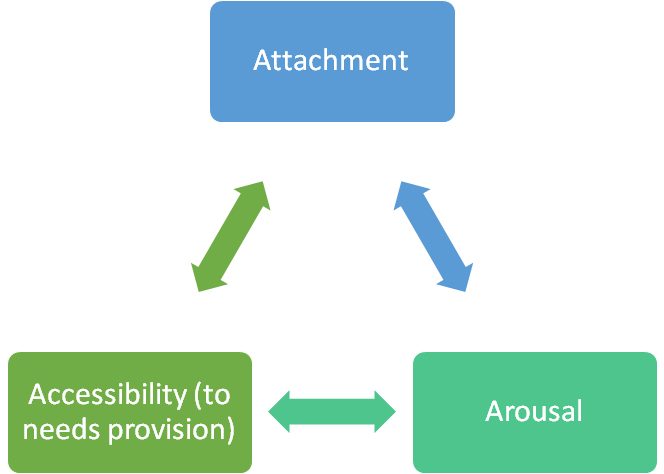

- The ideas or beliefs about themselves, others and their world that developed in the context of their first attachment relationships, and which influence their approach to life and relationships; and

- What they learnt about access to needs provision in their first care environment.

Trauma and Attachment and Learning

Children and young people with a history of trauma at home are prone to approaching life and relationships under the influence of negative ideas or beliefs about themselves, others, and their world. These negative beliefs are distressing enough. Paired with heightened arousal levels, the child is prone to anxiety and behaviours associated with the fight/flight/freeze response (see above).

In addition, these children and young people have often learnt that they cannot always rely on adults in a caregiving role to be accessible, understanding, and responsive to their needs in a reliable way. Again, this is frustrating for the child. They are commonly highly demanding. They can also be inordinately self-reliant. They can be a combination of both. Again, their behaviour is not always seen as stemming from their prior learning, and is responded to in such a way that reinforces their learning and maintains their frustration and distress (e.g. withdrawing/denying access, ignoring, disciplining).

To lower their arousal levels we need to also address their attachment beliefs and learning. It is beyond the scope of this talk to discuss this in detail. For more information and strategies I refer you to the following self-paced learning modules:

What can we do to make lower arousal the ‘normal state’?

Click here to enter the next page of this module.

To go back, click here.

To access a PDF version of this self-paced learning module, click here.