What do we mean by ‘trauma’?

I think the most appropriate place to start is what do we mean by trauma? In this context, trauma refers to an experience, or experiences, where the child or young person in your care was hurt or frightened or not responded to, such that their ability to cope was overwhelmed and they experienced significant and/or protracted distress. In this context, the trauma occurred at home in circumstances where mum and/or dad were finding life very difficult themselves due to mental health factors, relationship factors, addiction factors, or a combination of these, and where these circumstances negatively impacted the care they were able to give to their child. In circumstances where this was a very serious and ongoing problem, the child or young person in young care was placed away from home, ultimately with you. This was a protective intervention, but it was also one that comes with its own impacts from being placed away from mum and dad.

What is the impact of trauma on the developing brain?

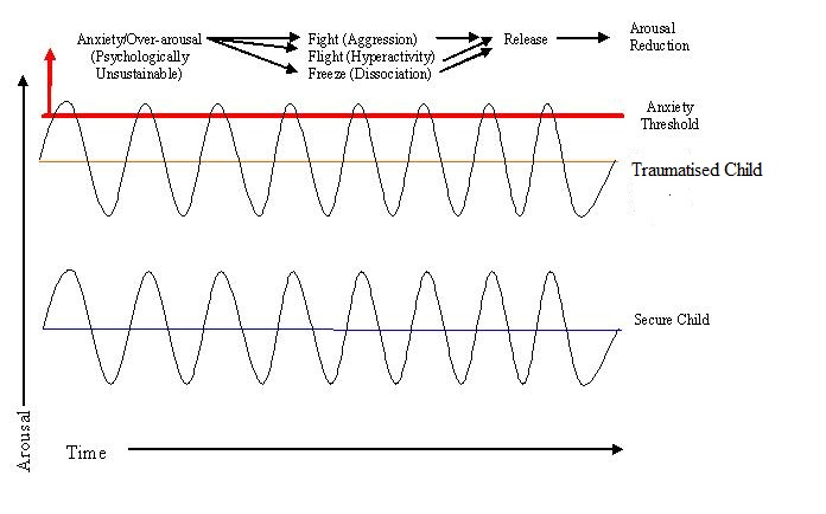

This trauma usually began early in the child’s development and shaped their development; particularly, their brain’s adaptation to their environment and experiences. The infant’s brain is known to be very sensitive to experience. The infant’s brain also tries to establish a stable internal state in response to external conditions; a state referred to in the scientific literature as homeostasis. When the infant is repeatedly overwhelmed and in distress, their ‘normal state’ becomes one of being on high alert. Physiologically, we speak of the brain being in a state of high arousal, where arousal refers to the level of activation of the child‘s brain and central nervous system. Thus, when the infant is repeatedly overwhelmed and in distress, heightened arousal becomes their ‘normal state’.

What happens when heightened arousal becomes the ‘normal state’.

When emotions are high, arousal is too!

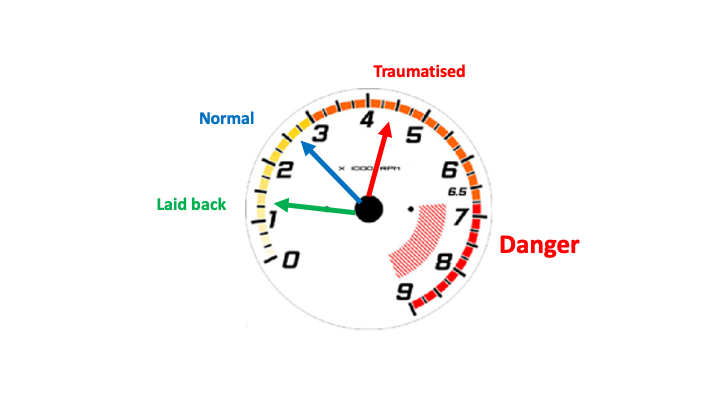

If we think of the brain, or central nervous system, as being like the motor in a car, the motor of children and young people who have experienced trauma runs faster than the motors of other children and young people who have not experienced trauma. This impacts them in a range of ways, including their emotions, their behaviours, and their learning. It leaves them prone to heightened distress and activation of the fight/flight/freeze response, which forms part of the brain’s protective system for managing heightened feelings of fear and distress. Unfortunately for them, the very behaviours that are deployed as part of the fight/flight/freeze response to manage feelings of threat and restore feelings of wellbeing are rarely seen as such, with the result that their fear and distress can be reinforced and perpetuated when adults become upset in response to the child’s behaviour.

Fight: controlling, aggressive, destructive, manipulative

Flight: running, hiding, avoiding, hyperactivity/agitation

Freeze: unresponsive, ignoring, not listening.

Mountains out of molehills and self-soothing

Children and young people whose motor runs too fast make ‘mountains out of molehills’. Seemingly little things bother them a lot. These can be sensory experiences, such as certain noises, textures, and tastes, even the way things (eg people) look. They may dislike certain foods, or the way certain clothes feel on their body. They may prefer to withdraw to their room or keep their hood pulled up and their earphones in. They are often hot (and bothered), and they typically struggle to get to sleep and stay asleep through the night. They may be preoccupied with accessing and eating food, as food is a source of comfort and oral soothing. They have an exaggerated need for consistency and can be quite demanding of this, as consistency and sameness are also soothing.

Heightened arousal and diagnostic formulations

Children and young people whose motor runs too fast struggle with, and are easily overwhelmed by, the demands of daily life. They may appear uncoordinated at sport and struggle academically at school. Their behaviour is often mistaken as a sign of an underlying disorder, such as oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, or a learning disorder. They often feel inadequate, helpless, and unworthy.

They do not, necessarily, have a disorder or lack ability or worth. They lack something else.

What do you think they lack?

Click here to enter the next page of this module.

To access a PDF version of this self-paced learning module, click here.