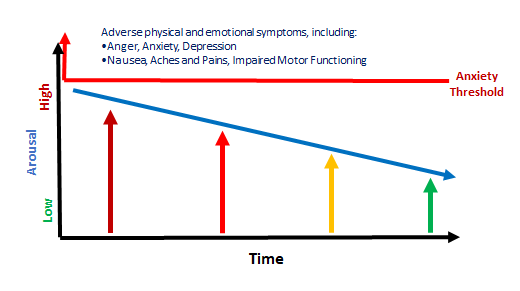

What can we do to make lower arousal the ‘normal state’?

- Music on at night

- Oral soothing

- Other sensory soothers

- Regulate ourselves (Make a therapeutic care plan. Follow it)

- Co-regulate

- Support engagement in regulating activities (e.g. learning/playing a musical instrument, art, sport)

Music on at night

Music is known to influence how fast our motor runs. Some music speeds it up; other music slows it down. Music that slows the motor includes:

- Music you like

- Music that is inherently relaxing (such as nursery rhymes and relaxing classical music)

Music can be used to slow the motor. My suggestion is that you quietly expose the child in your care to relaxing classical music while they are sleeping, either through a device placed in their room, or a device placed in an adjoining room. If you think that the child is likely to be distracted by the device, place it in an adjoining room. Wherever the device is placed, make sure that the music can only just be heard in a quiet room. Leave it playing all night.

You might say, but how will they know the music is playing if they are asleep? Well, our own brain is still attending to auditory stimuli while we sleep. If it did not, we would not wake up when there was a noise in the night. Relaxing classical music has also been played in operating theatres during surgeries. Patients who had surgeries where the music was on required less anaesthetic than those who did not have relaxing classical music being played quietly in the background. This shows that their brains were relaxed by the music, as well as the anaesthetic.

You can put the music on before they go to sleep. If they do not like the classical music, they can listen to music they like until they are asleep.

Compilations exist on platforms such as Spotify and/or other music streaming services (even, digital radio in some locations) that include classical music for sleep. We recommend trying this first. For older children and teens, they may prefer music they like, and this is okay.

If, after 3-4 days, the behaviour of the child or young person in your care is worse, stop playing the music.

Oral soothing

We are all oral soothers, to a greater or lesser degree. Oral soothing is common and is implicated in terms like “comfort eating”. When we are stressed we might eat, drink coffee or tea, bite our nails, or smoke a cigarette. Oral soothing is powerful, as even drinking a tea or coffee, or smoking a cigarette, relax us when we are stressed. Coffee, tea, and cigarettes contain stimulants that should wake you up rather than calm you down. Nevertheless, the opposite is commonly true.

Oral soothing has its origins in infancy. From the first moments of life, when the infant is distressed it is held and offered the breast or bottle. Whether they are breast or bottle fed, during feeding there is skin to skin contact, either via the breast or through being held. Skin to skin contact precipitates the release into the bloodstream of a hormone called oxytocin. Oxytocin soothes the nervous system. Hence, when the infant is being breast or bottle fed, oxytocin soothes them. Very quickly a strong association develops between having something in their mouth and calming down, such that they can be soothed with pacifiers and other objects placed in the mouth.

You might ask what happens in an inadequate care environment? It is likely that opportunities for oral soothing were inconsistent, such that a preoccupation developed. We commonly see this in heavily chewed clothing, fingers, and the like.

So, encourage the child or young person in your care to use straws when drinking from an open cup. Make your own healthy ice blocks or smoothies for them to chew on or suck. If they are old enough to do so, let them chew gum. The anticipated benefit is lower arousal.

If, after 3-4 days, the behaviour of the child or young person in your care is worse, stop implementing the strategy.

Other sensory soothers

Children often find their own objects that offer sensory soothing. It may be a favourite soft toy or a blanket. Some children are regulated by movement; others by a warm bath. Some like to wear headphones in busy, noisy environments. Where appropriate to do so, support the child’s access to these sources of sensory soothing.

Regulate ourselves (Make a therapeutic care plan)

The children in our care are sensitive and reactive to our own emotional state. We are part of the environment that their nervous system regulates in response to. Caring for children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life can be challenging. Self-care is important, and I recommend to you a module about self-care that I have included on the Secure Start website, here:

Self-care for carers of children and young people recovering from a tough start to life

An important part of our self-care endeavours is to have a plan for how we are approaching the caregiving role, and paying attention to how we are going. Paying attention is a form of mindfulness, for which there is much support in the scientific literature about its value in helping us to achieve and maintain a state of wellbeing. Paying attention to aspects of caregiving that help children and young people recover from a tough start to life supports our best endeavours in challenging times. Noticing the positive things we already know and do is reassuring (nb. It is also very helpful for the children and young people in our care, as I explain in the self-care module referred to above).

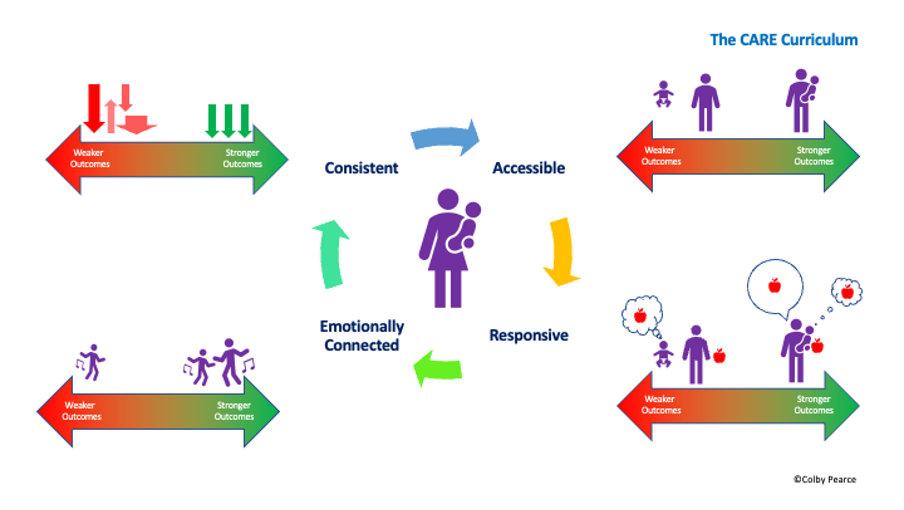

I encourage you to complete the following monitoring protocol over the next week. The caregiving behaviours reflected in it are drawn from the CARE Curriculum. For more information, refer to the CARE Cards. I anticipate that you will find that you already perform most, if not all the caregiving behaviours listed. To maximise the impact of your endeavours, we recommend that you fine tune your delivery of reparative care in one or other or both of the following ways:

- Implement each caregiving behaviour consistently, at a daily rate that you can maintain over time;

- Slightly increase the number of times you implement one or more of the caregiving behaviours, to enrich CARE.

Therapeutic Caregiving Protocol

In the table below, record the day and time you performed each caregiving behaviour.

| Caregiving Behaviour | Day and time you performed the behaviour | How can I make this more consistent? | How many times per day can I commit to performing this behaviour? |

| Performed a routine or ritual – consistency is calming | |||

| Checked in with the child before they did anything to secure my proximity and attention to them. | |||

| Spoke out loud the child’s thoughts, feelings, or intentions. | |||

| Responded to a need without the child doing anything to make it so. | |||

| Engaged in an activity where the child and I were emotionally connected, and where I helped them back to calm. |

Co-Regulate

he last item in the therapeutic care plan is an example of what we call co-regulation. Co-regulation involves tuning in to the child’s emotion and experiencing what they are. This is a natural process, if we let it. In a real sense, it is another example of the process of homeostasis, or the process by which your nervous system matches your internal state to the external conditions; including the emotions the child or young person is experiencing. This seems to occur naturally when we are engaged in a shared activity involving a shared emotion experience, such as playing a game, doing art or craft, or even eating. During such activities, we recommend that you regularly return yourself to calm. The child or young person will follow.

Repeated over and over, this process of co-regulation, where we tune into the emotions of the child or young person and lead them back to calm, is an important antecedent to them being able to regulate themselves.

Support engagement in regulating activities

Returning to the topic of mindfulness, immersing oneself in an activity is anticipated to have a calming effect and support a desirable state referred to as flow. Flow is akin to a meditative state. Supporting the child or young person in your care to engage in activities that result in a state of flow might also be expected to help them to maintain lower arousal levels.

Activities that support achieving a state of flow include playing a music instrument (one they are motivated and interested to learn/play), doing art or craft, building (such as with mechano or Lego), and writing. Gaming can also induce flow, though other factors might be at play that disturb flow.

Encourage the child or young person in your care to pursue an (appropriate) activity of interest as much as can be maintained over time. Such activities are also an important source of mastery which, in turn, facilitates feelings of wellbeing and better arousal levels.

A final word

Finally, the most powerful influence we have over regulation in the child or young person in our care is our relationship with them. We want to achieve a relationship that motivates them to self-regulate in consideration of their relationship with us. This can be easier said than done. The CARE Curriculum provides a way to achieve mutually satisfying, reparative, and regulating relationships.

Thank you for your engagement with this self-paced learning module. To access a PDF version of this self-paced learning module, click here.

To go back, click here.