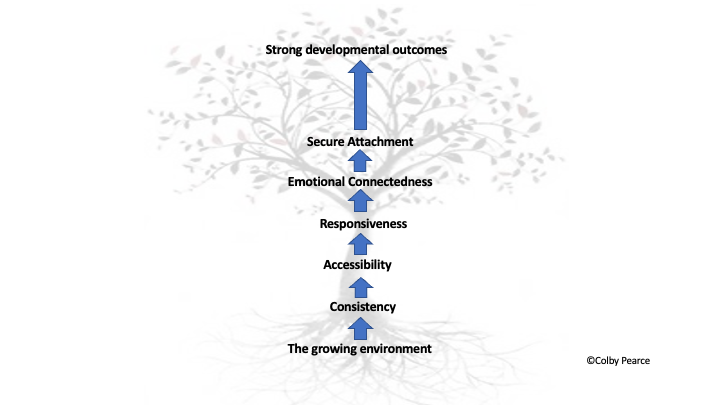

Parenting intentionally stands the best chance of supporting attachment security. Intentional parenting that supports attachment security involves the following:

- Being a consistent presence in the child’s life

- Being accessible to the child

- Being responsive to the child’s experience, and

- Being emotionally connected to the child.

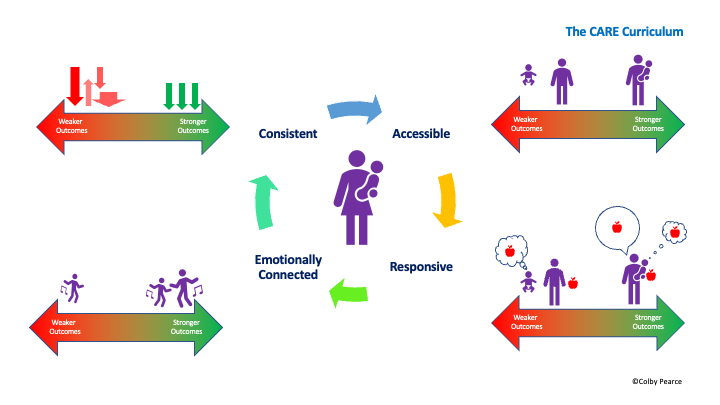

These aspects of intentional parenting can be summarised in the acronym CARE:

- Consistency

- Accessibility

- Responsiveness

- Emotional Connectedness

Hereafter, I will further describe each of these concepts, why they are important to attachment security (and development), and how to implement them intentionally.

Before I do, I want to acknowledge something. Depending on the age at which the child or children in your care entered your home they may have already formed attachment relationships and an attachment style. It is possible for children to form multiple attachment relationships. It is also possible for children to form different attachment relationships with different adult caregivers, depending on their experience of care from that adult. Where attachment relationships vary, the child’s overall attachment style and the way in which they engage with their world is a mixture of their attachment relationships. Where care has been inadequate or problematic, the child will need extra CARE to achieve a secure attachment style.

Reflection

What do you think is the attachment style of the child or children in your care?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

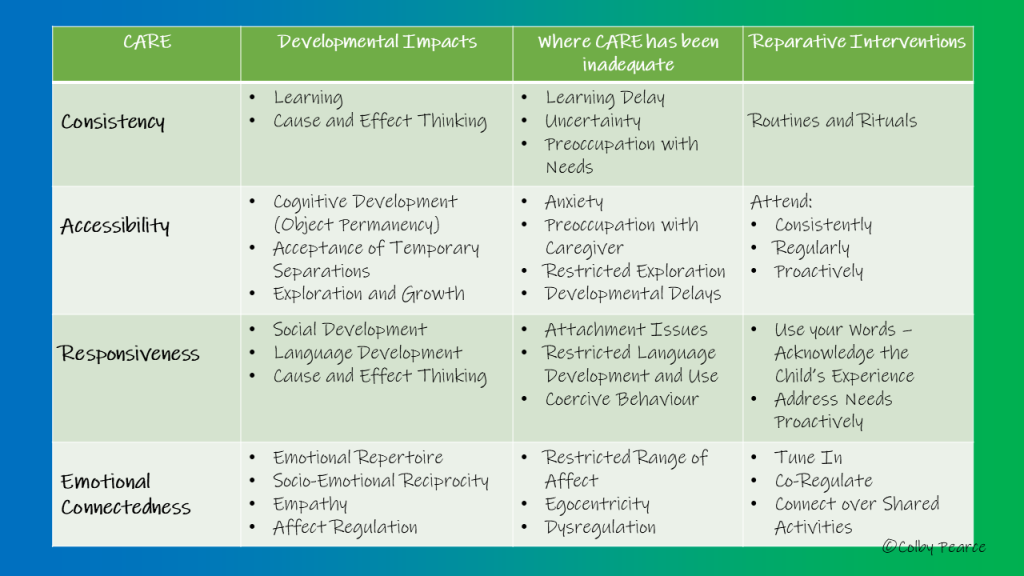

Consistency

Children form attachments to adults who are familiar and continuous aspects of their life, as well as being responsive to their dependency needs. For a secure attachment to develop, these adults must be involved with the child and respond to their dependency needs in a consistent way. They also need to be recognisable to the child, and so must present in a consistent way. Knowing that their recognisable adult caregivers are consistent aspects of their life and will respond to them in a consistent way supports confident exploration unhindered by anxiety about who is their caregiver.

Where there has not been a consistent adult or adults who cares for them, the child is unlikely to have formed a selective attachment to anyone. They can be excessively self-reliant, and/or indiscriminate in who they will seek a caregiving response from. They lack trust in caregiving adults, and in their own deservedness of care. They may resist care and may also be coercively controlling towards adults.

Reflection:

How can you make the experience of care more consistent for the child or children in your home?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

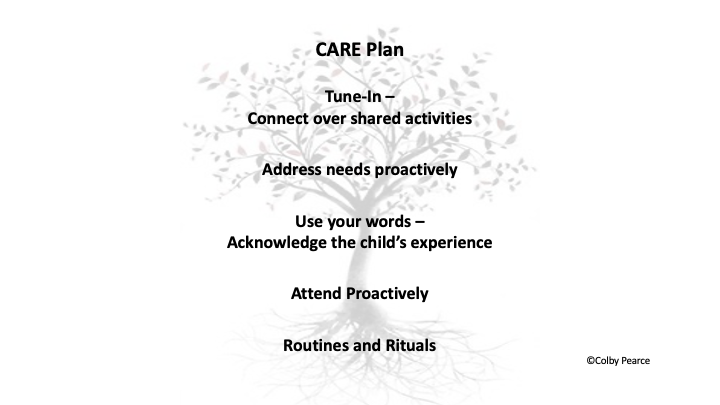

Recommendation: Implement a ritual or routine that will make the experience of care more consistent for the child or children in your home.

Accessibility

Children form attachments to the most available adults during the early developmental period. Children form secure attachments to adults who are accessible to them for comfort and needs provision on a continuous and consistent basis. Further, they form a secure attachment to adults who attend to them whether they are crying or quiet. These forms of accessibility support and reinforce a child’s understanding that they have a person who is responsible for their care, how to recognise them, and that their caregiving adult continues to exist during temporary separations. Knowing that they have a recognisable caregiver who is accessible to them even when temporarily separated supports a profound sense of comfort and reassurance for the child that allows them to get on with exploring their world without anxiety about the accessibility of their caregiver.

In contrast, when a child has not experienced their main caregivers to be consistently accessible to them, they struggle to accept separations and are commonly excessively demanding and preoccupied with their caregiver. During temporary separations, they are excessively anxious about where their caregiver is and who will respond to their needs. Both scenarios detract from the child’s capacity to explore and learn about their world and develop the capacities that support their success in life.

Reflection:

When does the child or children initiate interaction with you?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Can you anticipate this?

Recommendation: Get in first. Be there for them when they need you, before they do anything to make it so.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness refers to the actions the caregiving adults perform in response to the needs and experience of the child. Responsiveness extends from consideration of what is going on for baby/child? What is happening for them and what is their need, including the need or experience that is responsible for the behaviour you see? We do this naturally during the child’s preverbal years. (Incidentally, we also do this with our pets). When the child is verbal, we tend to encourage them to use their words more and more, which can be problematic, as I will explain in a bit. However, the child’s first experiences of the responsiveness of caregiving adults occur during a time when they cannot tell us in words about their needs and experiences that they require a caregiving response to. This spans much of the first three years of their life, before gradually reducing as the child becomes increasingly verbal.

When we come up with the answer to the experience or need the child has, and which may be evident in their behaviour or gestures, and respond to it, the child has their experience that their needs and experiences are understood, that they are worthy, and that they can rely on the caregiving adult to respond to them. Children who form a secure attachment experience their adult caregivers as consistently responsive to their needs and experience. Their caregivers regularly and accurately ask and answer in their head the question what is going on for baby/child (?), and then perform an action that responds to the need or experience of the child. The reflection on the need and experience of the child, and the associated response, is often accompanied by words, which is significant.

Children learn language in at-least three ways:

- Firstly, they learn language as a result of their caregivers expressing pleasure when, during their babbly, the infant says something recognisable as a word, such as the response of mum when the infant babbles Ma.

- Secondly, they experience their attachment figures speaking to them about their experience; that is, speaking the words the child would use if they had them. I am not trying to be funny, but we tend to do the same with our much-loved pets. When we do this the child gradually learns what words go with what experience or need. That is, they learn that the word happy is what goes with feeling happy.

- Thirdly, they watch and learn from others in relation to how they use language.

We are particularly interested in the first two. When a child’s caregivers are not consistent in these actions, the child will be relatively slower to learn language. Being slower to learn language and develop their vocabulary, the child will rely on behaviour and gesture to communicate about their experience and needs, long after the time when we would usually expect them to say what they need or what is going on for them. This can result in punitive responses, leaving the child feeling unheard and unsure of their worthiness. If this happens often enough, there can be long-term impacts to their self-esteem.

Reflection

What are some of the experiences and needs a child in your care has during the day?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

In ten words or less, what words might you use to express the child’s needs and experiences?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Recommendation: Say these words, regularly.

The second aspect of responsiveness is the action performed to satisfy the child’s need or experience. Sometimes, it is simply the words we say that communicate understanding of the child’s experience. Other times, it is what we do in response to the child’s need or experience; such as when we feed the baby at four-hourly intervals, burp them after a feed, and change their nappy regularly and when soiled. Responsiveness to the child’s needs and experiences supports the development of cause and effect thinking; that is, the understanding that when you do this that happens. This is important as it supports the child’s knowledge of how to access a caregiving response, thereby allowing them to explore and learn about other things.

Children form secure attachments to the adults who consistently respond to their needs and experiences through actions taken, as well as the words used. Securely attached children trust that their caregivers will respond to them when needed which allows them to explore their world, learn, and develop without anxiety about responsiveness to their needs.

Where responsiveness has been inconsistent and/or inadequate, these children approach life and relationships preoccupied with their needs. They can be excessively demanding or self-reliant; often both. They have learnt that they cannot always rely on adults in a caregiving role. This limits or impairs their exploration, with associated developmental impacts.

Reflection

What needs does a child in you care typically have during the day?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Can you anticipate some of these?

Recommendation: Address needs proactively, thereby promoting experiences that you understand and will respond to their needs without them having to worry that this will be so.

To recap, consistent responsiveness is optimal for secure attachment and a confident approach to life, relationships, and exploration. Where responsiveness has been inconsistent or inadequate, many aspects of the child’s development is impacted, including:

- Attachment security

- Speech and language development;

- Self-esteem

- Cause and effect thinking.

Emotional Connectedness

Emotional connectedness refers to those times when the emotions of the child and caregiver are in synchrony with each other. Emotional connectedness extends from the adult observing the child and allowing themselves to feel what the child is feeling. Often referred to as attunement, it is typically a natural experience to the emotion of another. Emotional connectedness typically flows from interaction and paying attention. In this sense, it can be intentional.

Emotional connectedness supports diverse aspects of emotional development. By tuning in and allowing connection to occur, the child begins to develop an understanding of the experience of others, which is an early building block for the development of empathy. The infant connects back with the experience of the adult and follows them where they go. This allows the adult to regulate the infant’s emotions before they are overwhelmed by them. This is commonly referred to as co-regulation, and it provides a safe space for the child to explore a range of emotions without fear of being overwhelmed by them, thereby developing a broad emotional repertoire. Through repeated experiences of being regulated by the adult, the child learns to regulate themselves. Through emotional connection with their adult caregivers, the child begins to regulate their emotions and behaviour in consideration of others in order to maintain connection, thereby providing the foundations for social competence and satisfying relationships.

Most important, emotional connectedness represents another opportunity for the child to feel heard and acknowledged in their experience, thereby supporting their sense of worth and trust in others.

Children form secure attachments to adults who are consistently attuned to their experience. Again, these children feel free to explore their world, learn, and develop free of unnecessary anxiety. In contrast, those children for whom emotional connectedness has been inadequate tend to show a restricted range of affect, restricted empathy, and restricted regulation of their emotions and behaviours in consideration of others. Too often, this serves to further distance them from others as they encounter disinterest and punitive responses to their so-called inappropriate behaviour.

Reflection

What activities do you and a child in your care engage in together?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Recommendation: Immerse yourself in the activity, and in paying attention to the child’s experience. Allow yourself to feel what they are feeling. Regulate to calm regularly.

Endnote:

Finally, I would like to finish this module by acknowledging what is, perhaps, the most important outcome of our endeavours – instilling a healthy sense of self-worth and deservedness of mutually-satisfying relationships among the children and young people in our care. For these two outcomes play such a significant role in the way in which children and young people who are recovering from a tough start to life approach life and relationships. A healthy sense of self-worth supports self-promoting decision-making and reduces the likelihood of self-defeating ones. A healthy sense of deservedness of mutually satisfying relationships supports self-regulation in consideration of the relationship the young person maintains with significant others in their life.

As we do with infants in a conventionally nurturing home, we need to build these kids up so that they can approach life with self-belief and positive expectations.

Click here to purchase the PDF Handbook for this self-paced learning module.