An article, written by Principal Clinical Psychologist Colby Pearce, which originally appeared on Colby’s blog site Attachment and Resilience.

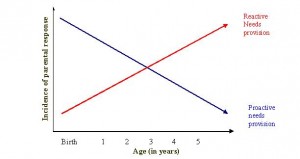

Perhaps the most little known and understood aspect of childhood trauma is the impact inadequate needs provision has on the child’s perception of how their basic human needs will be met in future, and their associated actions to satisfy their needs. Yet, over eighty years of psychology research clearly shows that inadequate and inconsistent parental responsiveness will promote an enduring preoccupation with needs and high rate and great persistence in securing needs provision. The same research also shows that simply changing the conditions for needs provision, such that a parent or caregiver responds consistently to the child’s signals regarding unmet needs, is not sufficient to reduce the child’s preoccupation with historically unmet needs or the rate and persistence of their need-seeking behaviours. So long as the parent or caregiver responds to the child’s signals regarding their needs, the child will continue to believe that they themselves are responsible for their needs being met. It is only through responding to the child’s needs proactively (that is, before they do anything to draw attention to their needs) that the child can develop an understanding that their needs are understood and important, and that they can depend on their caregivers to satisfy their needs. The consequences of this change in the child’s perceptions is anxiety reduction and opportunities for mutually-satisfying relationships through the lifespan.

Think of four common things you like to receive from others or have them do for you.

- First, think of what it feels like to have to have to ask.

- Now, think of what it feels like when someone provides before you ask.

- Now, think about what it feels like when sometimes it is offered and sometimes it is not.

Invariably, individuals prefer to receive something from others on a consistent basis and without having to ask for it.

Proactive needs provision involves providing experiences that build the child’s trust:

- That their needs are understood and important; and

- That their needs will be responded to reliably, predictably and without them having to go to extraordinarily lengths to control and regulate the behaviour of carers to make it so.

One of the most important lessons of the research referred to above is that a child whose needs have been met inconsistently is not easily convinced that their needs will be met simply because they begin to be responded to consistently.

For a time, such a child will only be convinced if their needs are provided for before they do anything to make it so.

This is the experience of infants. It is a universal characteristic of caregiving that supports attachment security and trust in the primary attachment figure.

During infancy, competent caregivers typically spend a lot of time thinking about the needs of the infant and addressing them proactively. It is only when children begin to attain language that competent caregivers increasingly rely on the child to verbally express their needs as part of their socialisation.

Children whose primary attachment figures were less than competent benefit from having their needs met in a proactive way again; thus promoting new learning that their needs are understood, important and will be responded to reliably, predictably and consistently. How else would they learn this?

I want you to think about some of the things a child in your care commonly asks for.

Children tend to ask for things like:

- Can I have something to eat?

- Can we go to the playground?

- Can I watch TV?

- Can I go on the computer?

- What clothes should I wear today?

- What are we having for dinner?

- Where are we going today?

- Who will pick me up from school?

Their questions and requests relate to a need or reasonable want:

- Can I have something to eat? (I am hungry; I need to know that there is food available; I need to know that you will respond to my needs)

- Can we go to the playground? (I need to blow off steam; I want to be entertained)

- Can I watch TV? (I want to be entertained; I need to know that I can access the TV)

- What clothes should I wear today? (I need to know that you will help me; I need you to look after me)

- What are we having for dinner? (I need to know that dinner will be available)

- Where are we going to day? (I need to know what is happening; I need to know whether I will be safe)

- Who will pick me up from school? (I need to know whether you will be there for me)

You can address these needs proactively by:

- Can I have something to eat? – Offering a snack before it is asked for.

- Can we go to the playground? – Scheduling regular visits to the playground and reminding the child of this before they ask.

- Can I watch TV? – Establishing a schedule for TV time and reminding the child before they ask.

- What clothes should I wear today? – Laying out the child’s clothes each morning before they ask. Laying out a choice of clothes and helping the child to choose.

- What are we having for dinner? – Developing a meal plan and making it visible to the child. Reminding the child to look before they ask (Have a look at what is for dinner). Scheduling days when they choose and/or help prepare the meal.

- Where are we going to day? – Developing an activity schedule and making it visible to the child. Reminding the child to look before they ask (Have a look at what we are doing today).

- Who will pick me up from school? – Developing a schedule regarding school pick-ups and making it visible to the child. Reminding the child before they ask.

Only set out to do what you can maintain over time.

The more needs you can anticipate, the better.

Other (often older) children do not ask. They do. For example, they:

- Take food from the cupboard/fridge without asking;

- Hoard food;

- Break their toys;

- Repeatedly call out or get out of bed;

- Act out demonstratively.

Their actions often communicate a need or wish:

- Take food from the cupboard/fridge without asking (I need to be reassured that I will get my share).

- Hoard food (I need to know that I will always have food).

- Break their toys (I need to know that nobody will take my things from me; I need to know how things work).

- Repeatedly call out or get out of bed (I need to know that you will be there for me during the night; I am afraid of the dark and I need to feel safe again; I need company as I am afraid of being alone).

- Act out demonstratively (I need space; I need to blow off steam; I need to know whether you will still be there for me after conflict).

You can address these needs proactively by:

- Take food from the cupboard/fridge without asking – setting aside food that is for their exclusive consumption.

- Hoard food – having fruit and other healthy snacks continuously available.

- Break their toys – providing a safe place for the storage of their toys; make it a rule that only the child can play with their toys; giving them things that they can pull apart.

- Repeatedly call out or get out of bed – having an extended bedtime ritual.

- Act out demonstratively – supporting their involvement in physical activities.

For more about how to parent children recovering from abuse and neglect in a therapeutic manner, please refer to The Triple-A Model; of Therapeutic Care.

A Tale of Three Mice: An Attachment Story

Once upon a time there were three mice.

Once upon a time there were three mice.

The first mouse lived in a house that contained, along with furniture and other household goods and possessions, a lever and a hole in the wall from which food was delivered. Each time the mouse pressed the lever he would receive a tasty morsel of his favourite food. The mouse understood that, when he was hungry, all he had to do was press the lever and food would arrive via the hole. The mouse took great comfort in the predictability of his access to food and only pressed the lever when he was hungry.

The second mouse lived in a similar house, also containing a lever and a hole in the wall from which food was delivered. Unfortunately, the lever in his house was faulty and delivered food on an inconsistent basis when he pressed it, such that he might only receive food via the hole on the first, fifth, seventh, or even the eleventh time he pressed the lever. This mouse learnt that he could not always rely on the lever and that he had to press the lever many times, and even when he was not actually hungry, in order to ensure that he would have food. Even after his lever was fixed he found it difficult to stop pressing it frequently and displayed a habit of storing up food.

The third mouse also lived in a similar house, containing a lever and a hole in the wall from which food was to be delivered. However, the lever in his house did not work at all. He soon learnt that he could not rely on the lever and would have to develop other ways of gaining access to food. This belief persisted, even when he moved to a new home with a fully-functioning lever.

Source: Pearce, C. A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder. London: Jessica Kingsley, 2009