Good morning. My name is Colby Pearce, and I am a practising Clinical Psychologist from Adelaide, South Australia. In my work I have been speaking with children and young people who have experienced early trauma, as well as their caregivers and other professionals who work with and support them, for twenty-seven years.

I am here today to talk about reflections I have made on the experience during infancy, of children and young people who are recovering from early trauma, based on my work.

Specifically, I am going to talk about the infant’s experience of trauma that is complex and relational, where there are multiple incidents of grossly inadequate care and/or harm, and where this occurs in the context of the infant’s early dependency relationships.

I am going to touch on a number of developmental impacts of grossly inadequate care and/or harm during infancy. I also intend to briefly touch on what a reparative environment looks like.

A key understanding here is that the trauma occurred in the infants first learning environment and impacted their learning about how the world works and what to expect of adults in a caregiving role. In a demonstrable way, and without reparative interventions, trauma in the first learning environment continues to profoundly affect learning and development throughout the growing years and life beyond.

In seeking to understand what is the infant’s experience of a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment, it is necessary to reflect on what is occurring for the parents of the infant. In my experience, in a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment parents are contending with one or more of (the following):

- Relationship stressors (Domestic/Family Violence)

- Mental Health Challenges

- Substance abuse issues

- Their own experience of inadequate parental care.

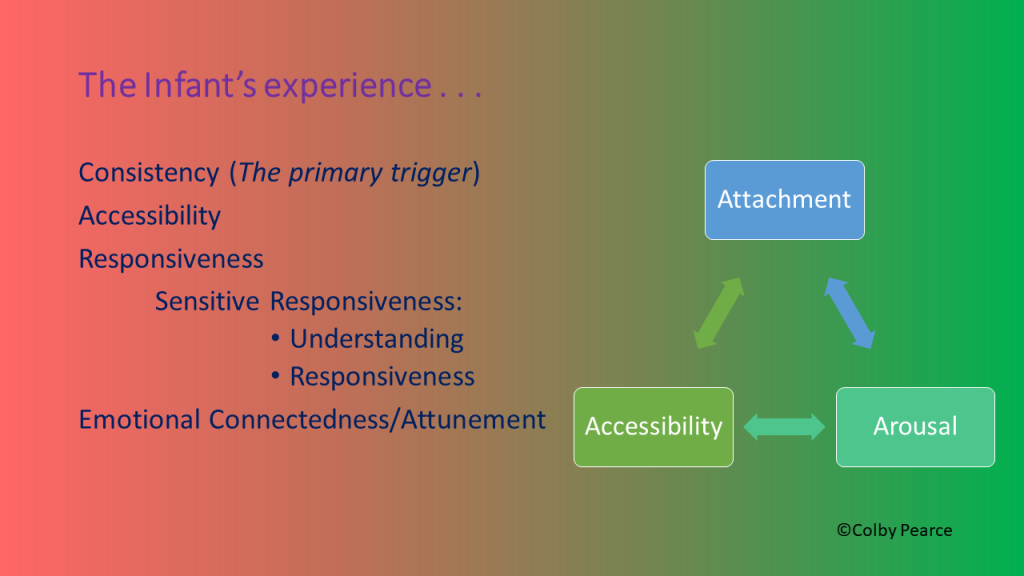

Consistency (The Primary Trigger)

The first aspect of the infant’s experience that I will speak to is consistency. Specifically, what is the infant’s experience of consistency in a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment, and what are it’s impacts on the developing child?

In a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment it is more accurate to refer to the infant’s experience of inconsistency. Two of the more commonly found inconsistencies in such environments are inconsistency of carer due to changes and disruptions in the infant’s care arrangements, and carer inconsistency due to the effect of their relationship stressors, mental health issues, substance issues, and poor parenting knowledge.

We know from psychological science that inconsistency is stressful. Those of you who have knowledge of the reaction of many school-aged children to a relief teacher will understand why I refer to inconsistency as the primary trigger. The central nervous system does not like change and unpredictability. It makes our motor, that is our central nervous system, run faster. It increases arousal. For the infant who is experiencing gross inconsistencies in parental care, it leaves them in a chronically and/or recurrently heightened state at a time when many aspects of central nervous system function are developing, and impacts that development.

Inconsistency also impacts learning, including learning about how the world works and what to expect of adults in a caregiving role. Inconsistency slows learning, conceivably leaving the infant in a prolonged state of uncertainty which is itself a central nervous system irritant.

Inconsistency of carer and carer inconsistency both disrupt the normal process of attachment formation, which has its origins in infancy and profoundly impacts the growing child’s approach to life and relationships.

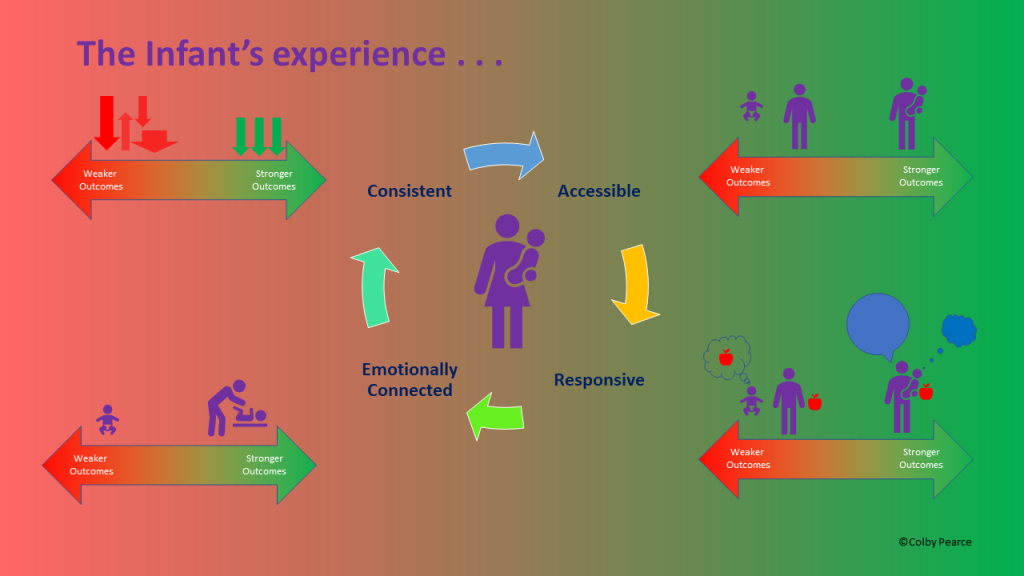

I refer to the figure on the right as the Triple-A Model. I developed this model to help inform our understanding of the impacts of early trauma and the affected child’s approach to life and relationships (Pearce, 2010).

Accessibility

In a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment infants experience their caregivers as inconsistently accessible to them. We see this in the ambulant child in the extent of preoccupation the child has with their contemporary caregiver, resistance to separation, and coercive behaviours to maintain caregiver proximity. They respond as though they are being (permanently) abandoned during temporary separations. It is my observation that this stems from an apparent disruption in the natural development of object constancy and permanency that are key developmental milestones during infancy, and which rely on a consistent caregiver who presents consistently during time with the infant, and returns often to the infant following temporary separations.

Where infants experience their caregivers as inconsistently accessible, attachment formation is impacted, especially when one considers the role of attachment in the development of the child’s emerging understanding of themselves, others, and their world. Inconsistent accessibility is also stressful and contributes to the infant being in a persistently and/or recurrently heightened state. Inconsistent accessibility impacts learning, including what the developing child learns about the accessibility of caregiving adults.

The combination of these factors leaves the child who has experienced early trauma prone to anxiety and associated behaviours (and responses from others) that perpetuate heightened states of arousal, maladaptive perceptions of self, other, and world (often referred to as internal working models, attachment representations, or schema), and experiences that confirm old learning about caregiver accessibility. Seen in this way, early trauma becomes self-perpetuating.

Responsiveness

In a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment the infant experiences inconsistent acknowledgement of, and responsiveness to their dependency needs. Too often, they do not feel understood or responded to. This leaves them stressed, impacts attachment security, and teaches them that they have to work hard to get their needs met, through inordinately demanding behaviour and/or precocious self-reliance.

Emotional Connectedness (Attunement)

In a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment the infant experiences inconsistent care and attention in relation to their emotions, including through the provision of a safe and contained space for exploration and help with regulating big emotions. In a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment the infant experiences reduced opportunity for connection with an adult who is sensitive to their experience and experiencing congruent emotion. Among the consequences of inconsistency in emotional connectedness and attunement are emotional defensiveness and a restricted range of emotions, difficulties with emotional control and self-regulation, and lack of consideration of the experience of others.

Where there has been inadequate emotional connectedness there are consequences in terms of attachment formation, arousal, and learning about how relationships work and what you can expect of them.

In short, in grossly inadequate and/or harming care environments there are major deficits in the infant’s experience of CARE – consistency, accessibility, responsiveness, and emotional connectedness (Pearce, 2016). This impacts the growing child in many ways, including in terms of attachment formation, arousal, and learning about the accessibility and responsiveness of adults in a caregiving role for needs provision.

In a reparative care environment, the child experiences consistent care from consistently accessible, responsive, and emotionally connected adults, where those adults:

- Are consistent and recognizable;

- Spend time with the child and attend to the child whether they are crying or quiet;

- Acknowledge and respond to the experience of the child (including their needs) in their words and actions;

- Share the emotions of the child and help them to back to calm.

A reparative care environment leaves the child feeling assured of their worth and of the value of human connection. In time, the goal is for the child to self-regulate their approach to life and relationships in consideration of their own inherent worth and the value of maintaining supportive relational connections with others.

In this presentation I have endeavoured to present key features of the infant’s experience of a grossly inadequate and/or harming care environment, how it impacts the developing child (Triple-A Model), and what a reparative care environment looks like (CARE). What children and young people need from professionals and caregivers alike is that we are mindful or our AURA; that is, the distinctive atmosphere or quality that is projected by us, our organisations, and by the parents and caregivers who are supporting a child’s recovery from a tough start to life.

It is vital that we consistently project an aura of accessibility, understanding, responsiveness, and attunement.

Thank you.

For more about Colby and his work visit:

Secure Start® (business website): https://securestart.com.au/

Attachment and Resilience (Personal Blog): https://colbypearce.net/

Click here to purchase a PDF of this presentation (and others).

References:

Pearce, C.M. (2016) A Short Introduction to Attachment and Attachment Disorder (Second Edition). London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Pearce, C.M. (2010). An Integration of Theory, Science and Reflective Clinical Practice in the Care and Management of Attachment-Disordered Children – A Triple A Approach. Educational and Child Psychology (Special Issue on Attachment), 27 (3): 73-86